AMMs as the new form of liquidity

By Joao Baptista, Jacob Pedersen

Resumé

This paper aims to explain the role of Automated Market Makers (AMMs), exploring the historical progression of financial markets that culminated in liquidity challenges solvable by this innovative approach. It examines AMMs as ERC721-based liquidity provider (LP) positions, focusing on their evolution and the groundbreaking innovations introduced through successive versions.

A notable development is the introduction of Uniswap v3, which enables concentrated LP positions designed to optimize on-chain liquidity within specific price ranges. This advancement highlights the efficiency and precision offered by these mechanisms in addressing liquidity issues.

Ultimately, the paper seeks to equip readers with a comprehensive understanding of the importance of these assets, emphasizing why LPs represent a time-tested solution to contemporary global liquidity problems.

Introduction

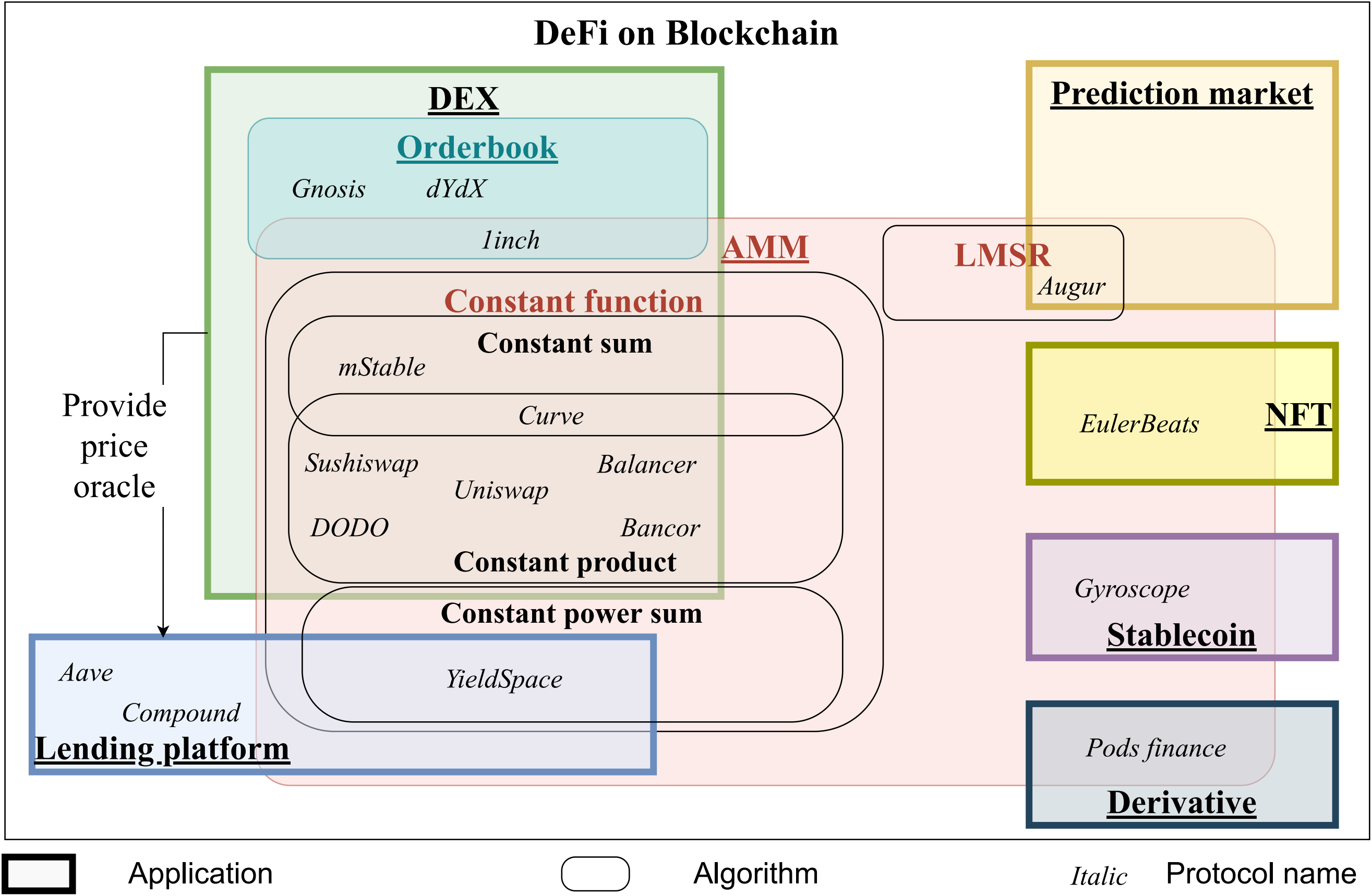

The rise of blockchain popularity and functionality has catalyzed the evolution of financial systems into decentralized, permissionless, and algorithmically governed architectures. Fundamental to this transformation lies a class of smart contract-based algorithms known as Automated Market Makers (AMMs). AMMs facilitate peer-to-peer asset exchange without the need for traditional intermediaries or centralized order books, crucial to a decentralized functioning world, meaning that manually matching traders or using centralized systems are replaced by mathematical formulas to determine asset prices and ease continuous liquidity provision. The automation of market-making through AMMs is one of the most profound innovations in the decentralized finance (DeFi) movement.

Traditional and centralized financial systems rely on professional market makers to provide liquidity and set bid-ask spreads in a centralized order book. AMMs disrupt this model by democratizing liquidity provision and implementing transparent, auditable pricing mechanisms. Anyone can become a participant and liquidity provider (LP), contributing capital to pools governed by well-known algorithms that ensure fairness and verifiability on-chain. The concept and intellectual foundations of AMMs can be traced back to the theory of market scoring rules and the work of Robin Hanson, who developed the Logarithmic Market Scoring Rule (LMSR) to manage prediction markets. These early conceptual frameworks posited that pricing could be dynamically adjusted using logarithmic scoring functions, rewarding traders for improving market predictions while supporting liquidity.

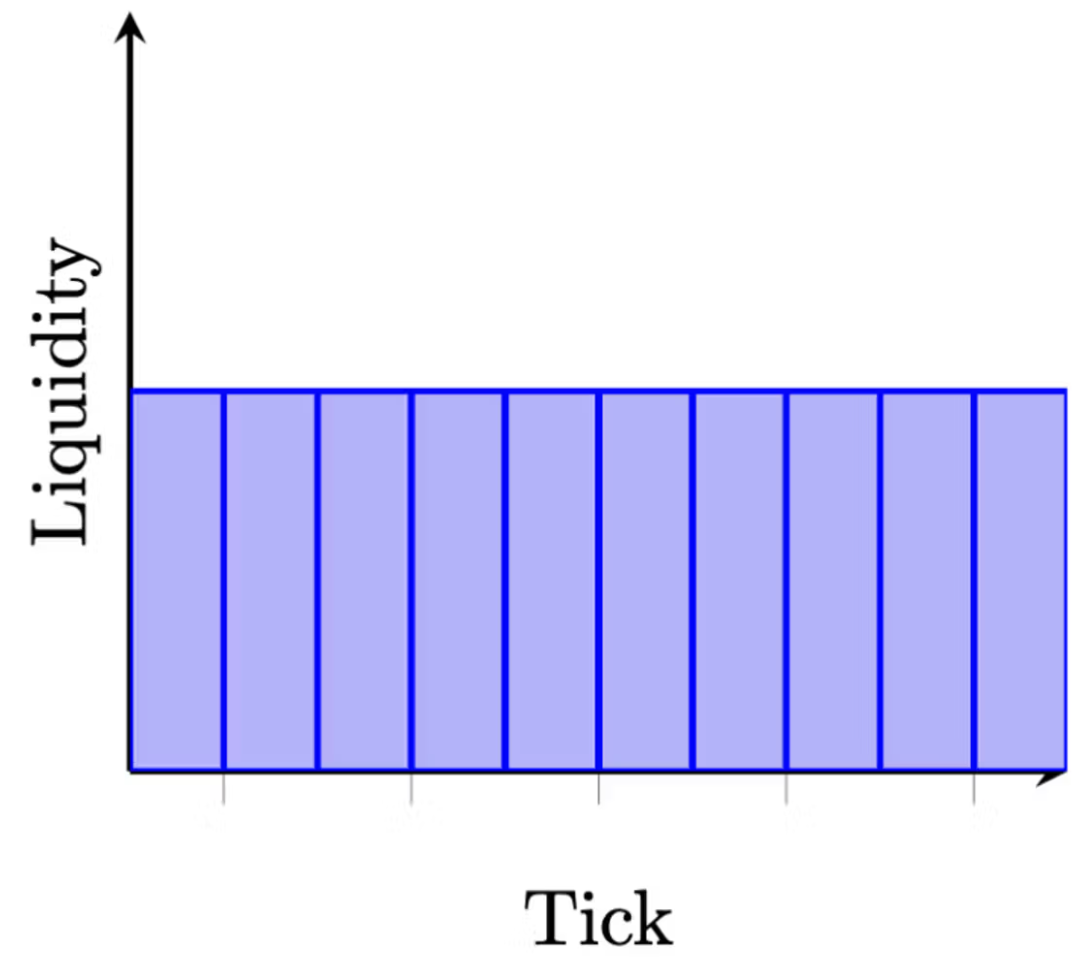

These concepts evolved into AMM algorithms, initially with Uniswap’s constant product formula setting a new standard for decentralized exchanges (DEXs). Launched in 2018, Uniswap v1 allowed users to swap ERC20 tokens via Ethereum smart contracts in a single transaction in ETH-ERC20 pools, with liquidity providers (LPs) depositing capital to earn trading fees. Uniswap v2 soon followed, introducing improvements such as ERC20-to-ERC20 pools, reducing gas cost and enabling direct token swaps and time-weighted average price (TWAP) oracles, while still representing LP positions as fungible ERC20 tokens - the constant product formula still working. Despite these upgrades, both versions faced capital inefficiency, as liquidity was passively spread across an infinite price range.

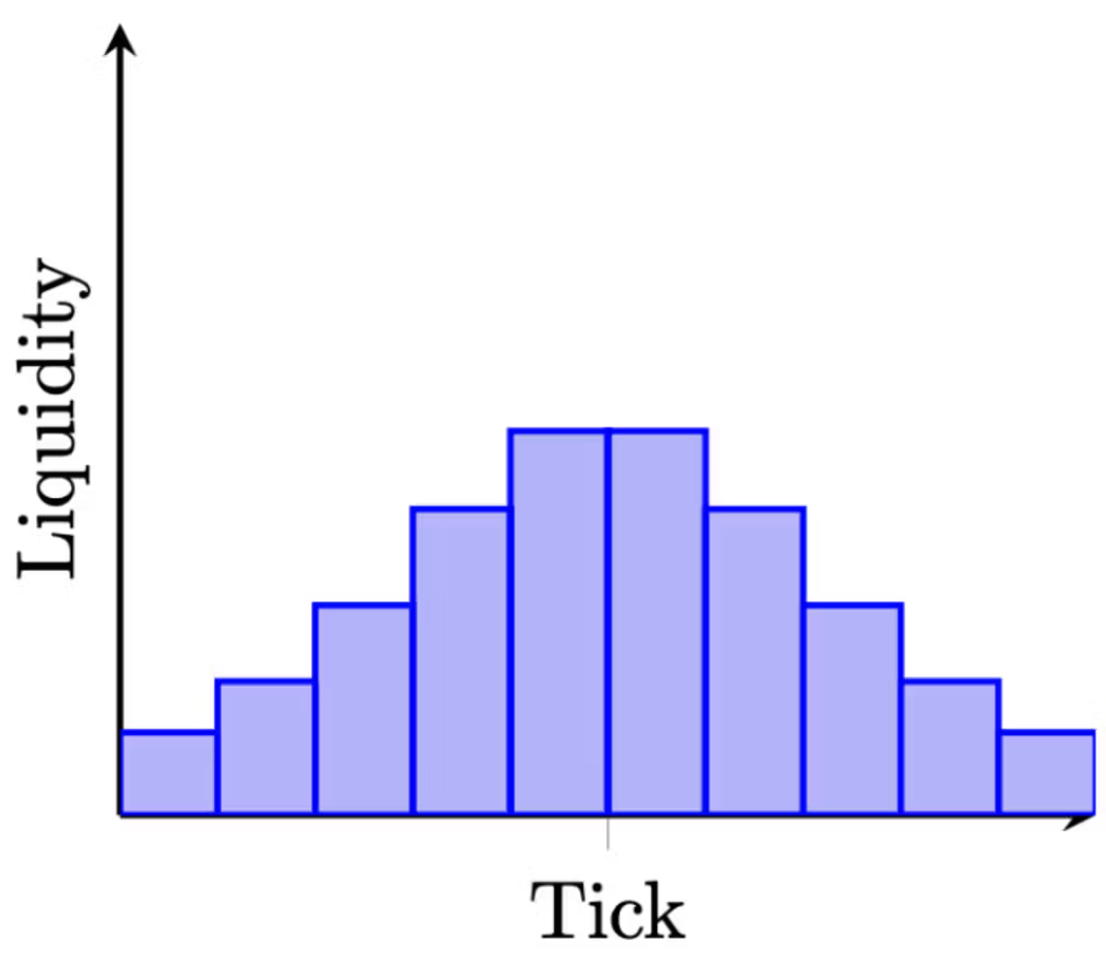

Uniswap v3 addressed this limitation by introducing concentrated liquidity, allowing LPs to allocate capital within custom price bands. This design made each LP position unique, defined by its price range, token pair, and fee tier. The representation of this LP capital is no longer possible using a fungible ERC20 token, where each position is unique from the other. Uniswap v3 adopted a non-fungible token (NFT) with the ERC721 standard to represent these individualized positions on-chain.

The primary advantage of having a fungible asset - ERC20 token - that represents the LP position in Uniswap v2 was their fungibility and ease of fractionalization: any token could be split or combined, ensuring that all positions were identical and interchangeable. With the innovation of concentrated liquidity in Uniswap v3, where liquidity providers specify custom price ranges, LP positions become inherently unique and can no longer be repressed by fungible ERC20 tokens. Each position is minted as an NFT whose fungibility is no longer a benefit; this asset still offers several significant benefits. It provides unambiguous on-chain proof of ownership for each discrete liquidity position; facilitates seamless transfer of LP positions between wallets or contracts; tokenizing positions as NFTs enables real-time tracking and management of individual LP allocations, as off-chain tools can query each NFT's metadata directly. Moreover, because each LP NFT has transparent and verifiable on-chain characteristics, these positions can now be used more readily in broader financial applications.

AMMs are the innovation that powers the evolution of decentralized finance (DeFi), serving as a foundational pillar for efficient market operation. Developments in AMM design, most notably led by the Uniswap foundation, have been instrumental in driving the growth and maturation of crypto markets.

AMMs and decentralized exchanges (DEXs) are distinct yet complementary concepts. An AMM is a pricing algorithm that facilitates swaps without relying on traditional order books, while a DEX is a type of platform enabling peer-to-peer swaps on a blockchain. This distinction allows for varied implementations: order book-based DEXs, such as Dydx and now Hyperliquid, which match buy and sell orders; AMM-based DEXs, like Uniswap and Raydium, which use algorithms like the constant product formula to set prices; and AMMs integrated into non-DEX applications, such as prediction markets or stablecoin protocols, where they manage liquidity and pricing. Understanding these configurations highlights the flexibility of AMMs and DEXs in DeFi.

Historical evolution of liquidity promoters participants

Since the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the internet boom has driven a profound paradigm shift: the rapid and pervasive transition from physical to electronic markets. Trading has moved from open-outcry pits that required face-to-face interaction to digital venues unconstrained by geography.

NASDAQ was the world's first electronic stock market (in 1971), functioning as a “quotation system” or “bulletin board” only, and didn’t execute trades. The first innovation was to provide automated, centralized stock quotes for the vast and fragmented over-the-counter market, which had previously relied on phone calls between dealers. Promoting transparency, NASDAQ was able to lower the bid-ask spread, making the market more efficient.

Pit-traders at exchanges resisted moving to electronic trading for decades, but when the ICE began offering nearly identical oil contracts forced all executives to adopt electronic trading on CME’s Globex system in 2006 to survive.

This shift has introduced new requirements. Whereas buyers and sellers once had to gather in a single physical location, they are now distributed globally. Electronic exchanges aggregate these participants, matching orders automatically according to price-and-time priority. Markets have become bigger and faster, with more participants and transactions. New players have emerged – High frequency traders – because many markets operate independently, HFTs exploit arbitrage opportunities created by these conditions.

As markets became interoperable and traders sought to open or close positions as quickly as possible, another player type emerged - the market maker. These participants provide liquidity and depth to markets by continuously quoting both a bid and an ask price; without them, buyers and sellers have to wait for a counterparty. Without market makers, markets would be illiquid and volatile. Buyers will have to wait for a seller to appear at the same time with matching price and quantity, leading to insufficient transactions and inefficient price discovery.

The competition between market makers is crucial to improve market efficiency, forcing spreads to narrow, resulting in better prices for investors. Monopolistic and total control of the order book from a single market maker increases a conflict of interest between managing the orderbook and their accounts, leading to several SEC enforcement actions against specialist firms for improper trading.

Market-making has been a fundamental concept of financial systems. In traditional finance, market makers act as intermediaries, providing liquidity, profiting from fees and spreads, and supporting efficient market function. They control expensive hardware and location to manage speed. Their compensation reflects adverse selection risks, administration costs, and inventory holdings. However, reliance on centralized entities entails drawbacks such as opaque pricing and vulnerability to shifts in market conditions. Algorithmic market-making systems seek to mitigate these dependencies, risks, inefficiencies, and costs created by centralized market makers.

Liquidity is directly related to market efficiency, given market makers and HFTs’ considerable power; if they disappeared overnight, the entire market would face significant risk. Market’s microstructure is no longer shaped by a multitude of brokers but is now heavily influenced, and in many ways controlled, by a small cohort of technologically supreme high-frequency trading firms. The market share of these participants grew to over 50 to 60% in volume, distributed in a small number of operational firms. The majority of the revenue made is even more concentrated in small groups of firms – Citadel, Jump, Virtu, HRT, Two Sigma, as examples. It is a market where a single winner takes all, primarily based on speed.

Using trading metrics, these firms undeniably provide liquidity, narrow spreads and deep order books. But the primary criticism is that HFT generates “ghost liquidity”, meaning the same algorithms that post billions of dollars in quotes can cancel those quotes in milliseconds. Practices like “quote stuffing”, placing immediately cancelling huge numbers of orders, creating misleading impressions of market depth that are not genuinely available for other traders to interact with. Examples like the 2010 flash crash, where HFT liquidity vanished precisely when it was most needed, exacerbating the market’s freefall. Creating the illusion of being more liquid and efficient than ever in calm conditions, but more systematically fragile in tough situations, when liquidity is programmed with a homogeneous strategy.

These notions make it clear that in calm situations, these firms are promoters of liquidity and market efficiency. But in volatile situations, based on the concentration of liquidity in a small cohort of players, the market is more fragile, with lower liquidity and higher risk. The trend of the market orderbook concentration tends to grow with the evolution of AI and machine learning in market-making businesses. The only solution that emerges in a decentralized world is with the use of AMM – automated market maker – and DeFi.

AMM is the movement of radical reimagining of liquidity provision. Eliminates the deep control of market-making business and reduces the monopoly control of the algorithms. All players have the same level of competition and share the revenue. AMMs are not firms; they are protocols, pieces of self-executing code (smart contracts) that run on public blockchains, like Ethereum. AMM facilitates trading through liquidity pools, funded by users known as liquidity providers (LPs), who deposit their assets into the pool. It is permissionless and non-custodial, meaning anyone can become a liquidity provider and earn a share of the trading fees, and users always retain control of their assets. 24/7 with liquidity always available as long as there are assets in the pool – market makers in this model are replaced by a protocol.

Historical evolution of AMM

Robin Hanson’s work in 2002 on prediction markets titled Logarithmic Market Scoring Rules for Modular Combinatorial Information Aggregation, later influenced automated market makers in DeFi. The Logarithmic Market Scoring Rule (LMSR) is a pricing mechanism for the prediction market that adjusts prices dynamically based on the net position of the market. It was introduced in a way to maintain liquidity through a predefined cost function, which laid the theoretical groundwork for AMMs, and mathematical rules could replace centralized and human intermediaries in setting prices.

Since the paper of Robin Hanson, Vitalik proposed putting AMMs on a blockchain – laying out path-independent pricing curves and liquidity pools in curves and liquidity pools, in the paper “On path independence”. Bancor was the first team to deploy the first AMM system as constant-product AMM pools (meeting the formula ) on Ethereum. This flow of events created the new market structure, created the decentralized finance primitive as it is today, with AMMs being the drivers of liquidity.

Hayden Adams, founder of Uniswap, levelled up this use case. Uniswap is a decentralized exchange that most drives this innovation forward.

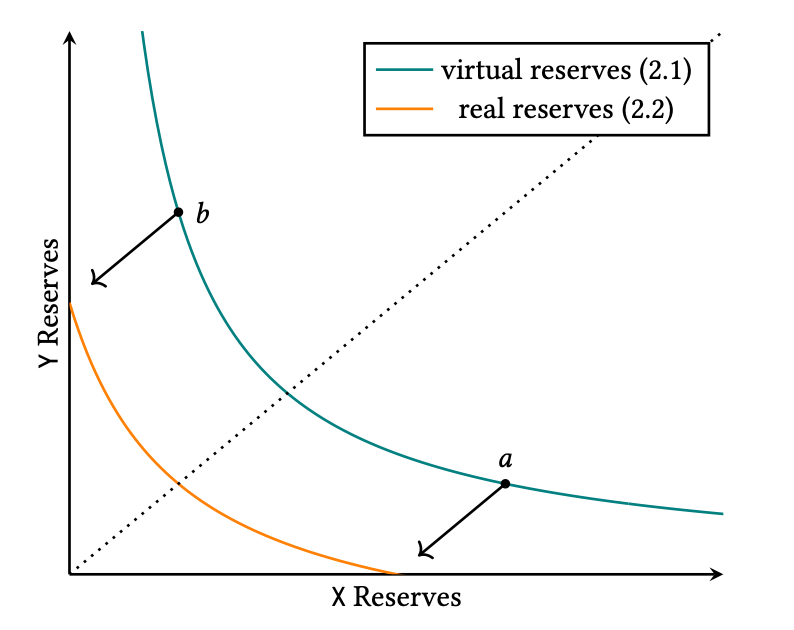

The release of Uniswap v1 in 2018 was the first major implementation of an AMM on Ethereum. The design was simple; a constant product formula called the constant product market maker (CPMM) where the product of two reserves of assets ( and ) would always remain constant (). This function is expressed as automatically adjusting prices in response to trades, but limiting the types of swaps you could complete on a DEX. The formula meant that the product of token quantities in a liquidity pool must remain constant. When a pool was conceived, a liquidity provider had to deposit equal amounts of the two tokens, setting and in return, the price of the asset. The limitations were that all liquidity was evenly distributed across the entire price spectrum from zero to infinity, which made capital allocation inefficient.

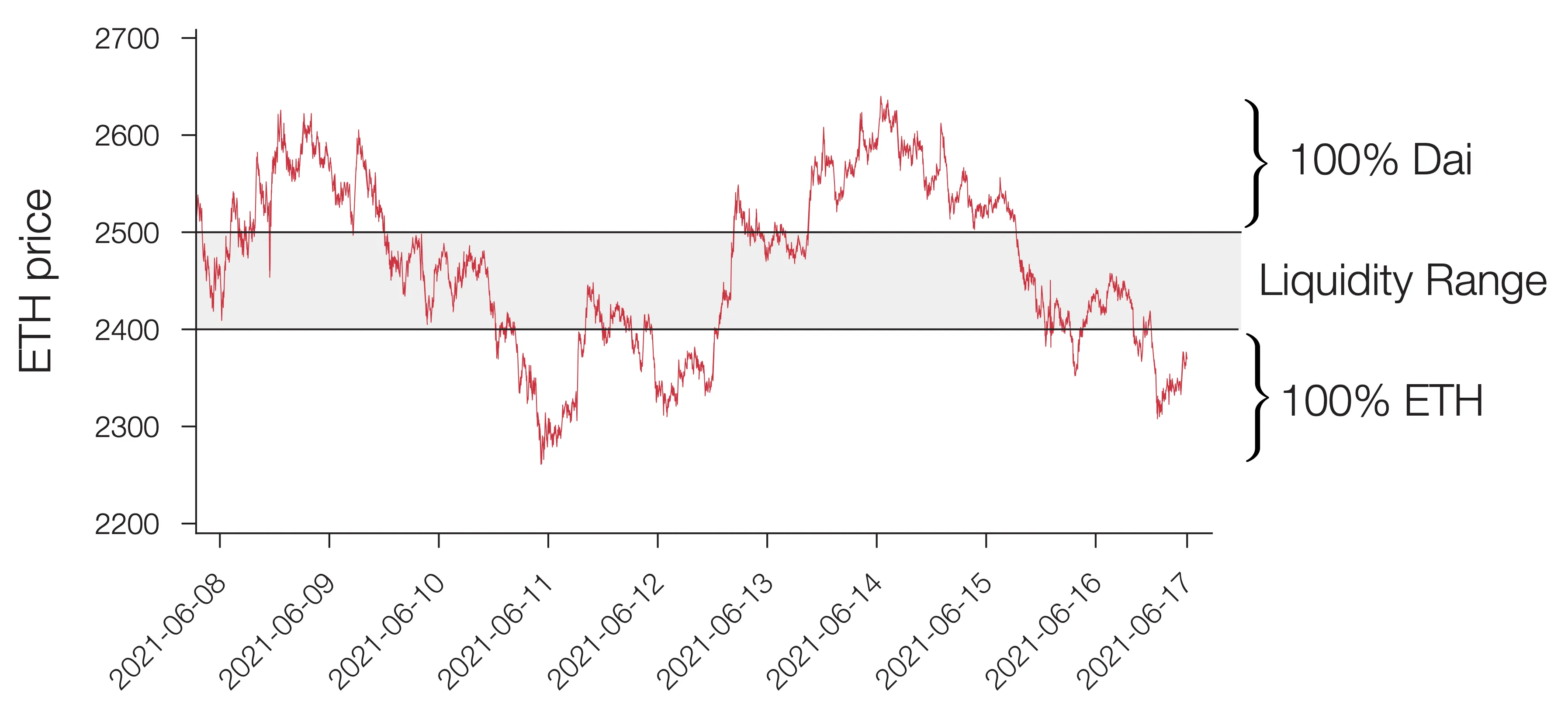

Uniswap v2 launched in 2020, improving upon the first iteration by enabling direct ERC20 to ERC20 token swaps along with integrating time-weighted average price (TWAP) oracles. This model, while democratizing access to liquidity provision, led to poor capital efficiency. Most LP capital remained idle, particularly in stable asset pairs where prices fluctuated within narrow bands. Then in 2021, Uniswap v3 was released, introducing the concept of concentrated liquidity to allow LPs to specify the price ranges in which they wished to provide liquidity, and their capital would be active. This resulted in deeper liquidity near current market prices. Liquidity positions consisted of unique values for the range, token pair, and fee tier; these parameters could not be represented by fungible ERC20 tokens and instead needed non-fungible token (NFT) representation using the ERC721 standard. Now, every LP position becomes a distinct financial instrument rather than an interchangeable token as it previously was; this allows for specific risk-return profiles to be assigned.

Uniswap v4 unlocks “hooks”, a singleton architecture – an unlimited number of markets can be created using just one smart contract - and a flash accounting system. This update provides unprecedented levels of customization, dramatically reducing gas fees. Hooks are external smart contracts that can be “hooked” into a liquidity pool at various trigger points (such as before or after a swap, or when liquidity is added or removed). Unlocks dynamic fees based on market volatility or other conditions, optimizing returns for LPs and offering better rates for traders; onchain limit orders; TWAMM, time-weighted average market making systems and other strategies can be built now on Uniswap pools.

Importance of AMM LP

This innovation has 2 core importances: 1. Is the liquidity of decentralized finance; 2. Serve as a hedge to the systematic risk of traditional markets, concentrated in a market maker structure. And these 2 core importances are crucial to improve the efficiency of the modern, digital, electronic market, co-working as a complementary solution to solve the constant problems of liquidity.

With the evolution of the digital market, liquidity-driven financial crises have happened more frequently. Historically, since the year 1900 and before 2000, we have had only 5 liquidity crises: 1. Panic of 1907; 2. Wall St. Crash and the Great depression in 1929; 3. US “credit crunch” in 1966; 4. “Black Monday” crash in 1987; LTCM near-failure in 1998. But after the year 2000, we have already had 4 crises in only 24 years, with a crisis happening over 5 years: 1. Global Financial Crisis of 2007; 2. Euro-area sovereign-debt and bank liquidity crises in 2010; 3. “Dash-for-cash” COVID shock in 2020; 4. US regional bank runs in 2023. The systematic risks are imminent with the growth of crises. Having a non-centralized solution to maintain the liquidity solid and less volatile is crucial in today’s market.

Automated market maker liquidity provider positions serve as the foundation upon which decentralized exchanges (DEXs) operate, ensuring that markets remain liquid, trades can be executed at competitive prices, and capital can be efficiently deployed in a decentralized ecosystem. With the increase of capital in LPs, directly increase the liquidity attached to the specific tokens. The higher the liquidity, the bigger the amounts investors/traders can operate with, without any sacrifice of performance, price impact. With the Uniswap v3 innovation, LPs can concentrate their liquidity into specific ranges, promoting even more liquidity to those ranges, increasing the market depth.

Comparing this liquidity to the centralized market makers, in decentralized finance, you have a transparent onchain tracking and verification of the liquidity. You can see and verify the liquidity for that specific token, and you can predict the price slippage of your order to the price impact based on the AMM conditions with a higher probability of success. Each position is attached to an NFT that encapsulates position-specific data such as deposited liquidity amount, active price range, fee tier, and accrued fees, making it possible to assess the position’s real-time exposure and performance with precision.

This real-time accessibility to position metadata significantly improves operational efficiency compared to traditional capital markets, where asset verification, risk modeling, and exposure tracking involve layers of friction, intermediaries, and settlement delays. In contrast, AMM LP NFTs offer on-chain, instant access to performance metrics and composability with other DeFi tools. These advantages highlight their potential as capital-efficient instruments, not only for yield generation through fees but also for contributing to the development of financial tools such as automated risk analytics, portfolio management strategies, and potentially, lending frameworks.